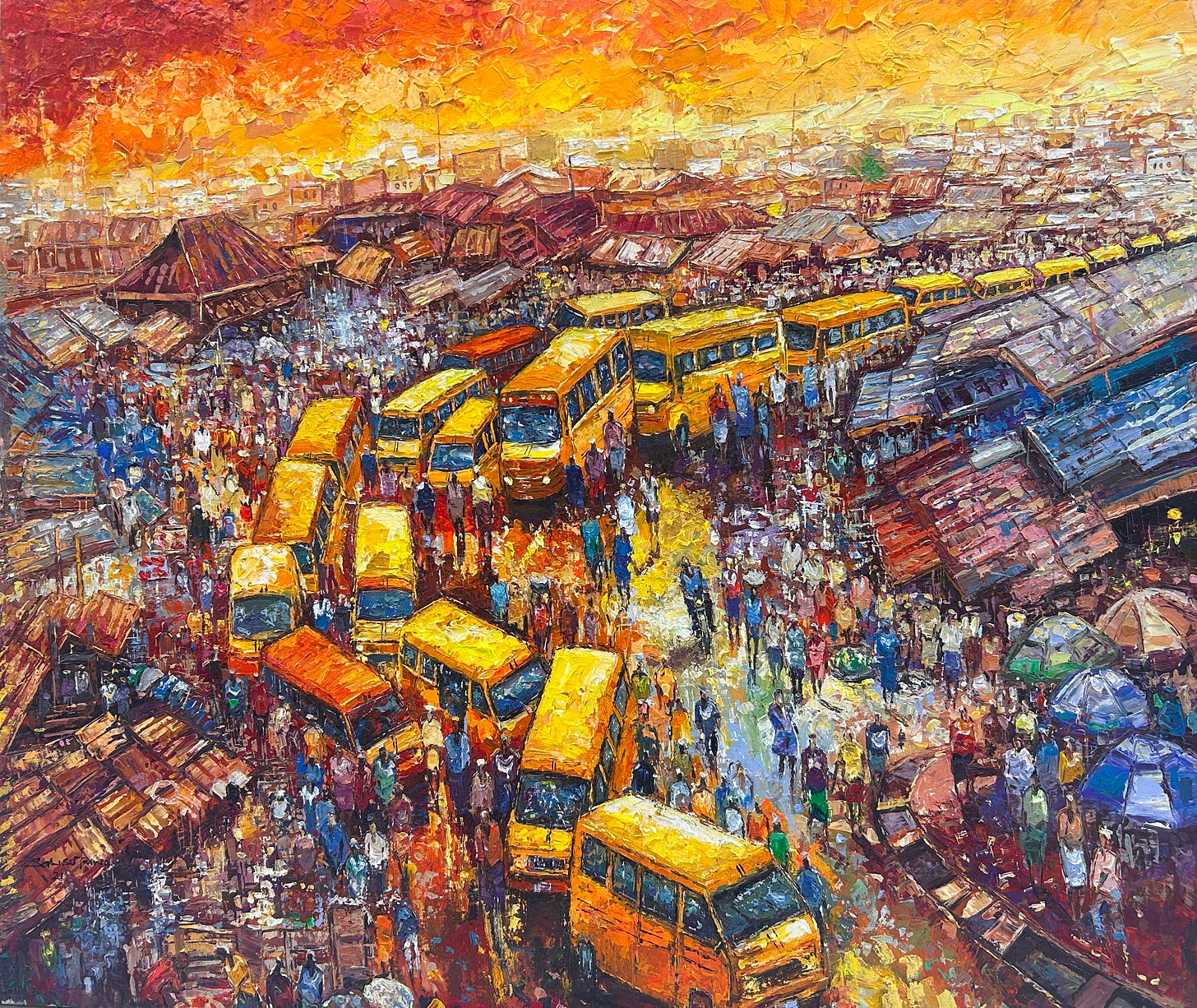

The thing that hits you most powerfully on getting immersed into Lagos, is its high density. Not only as a matter of concentration of people, but anything and everything detectable to the senses—tastes, odors, sights, noises and feels—take on an intensity that is orders of magnitude greater than can be experienced in your ordinary city elsewhere.

I travelled there this summer.

After a missed direct flight, rerouting for a short layover in Paris, my family and I landed in the Lagos night at Murtala Muhammed International Airport around 9:30pm—12 hours after we should have been there.

For an African living in the West, traveling in Africa can feel like an invitation to judge. Surveying things with a scholarly detachment in the guise of a cultural anthropologist overflowing with wisdom, and snappily ticking off where things should be better in the tableau before your eyes.

It is especially true for Lagos; an in your face city like no other. The city all but solicits this kind of cursory scrutiny. In all essentials, it is unlikely you will see something in another city that you will not see in Lagos: no act in any other city on earth that does not have its counterpart in this 24/7 pleasure seeking city shining its proud lights on the Bight of Benin. Home to an elite class decked out with chauffeurs, maids, gardeners, security at the gate and away from home, and the whole apparatus of appurtenances that attend moneyed classes, and then some—replicating in their lives an ecosystem of perks, appearances, social codes, and excess that the silver and small screens bring to them.

One would be forgiven for assuming old school British and their class ways still reign here. For hammocks suspended on shoulders in the 1800s we now have chauffeur driven tinted-window luxury SUVs.

Lagos is the exemplar city. The city that contains within it a multitude of other cities. It has swanky midtown high rise towers and yachts on the waterfront, luxury SUVs forcing their way through traffic jams behind private escorts flashing police lights, found-material shantytowns, humble congregations of rusty corrugated metal sheets and plastic covered shacks by the roadside and rail tracks.

This is only what you see in the daytime. If you dare to taste night time Lagos, word on the street is you are taking in your two hands your precious life—and God help you.

In these parts, the proper exclamation for such bonehead ideas is in fact JESUS!

Questions that arise

In the first minutes of leaving the airport extending into the first few days, while the senses were still keen, primed to catch fleeting acts that are everyday experiences for the Lagosian, I welcomed and marinated in all questions thrown at me by the scenes I was taking in.

As an African who has spent the better part of more than two decades in the USA, what is the proper attitude, the fitting deportment towards the life teeming and happening all around?

Is it pity for the hard life? Pride at the enterprise and entrepreneurial energy on display? Contempt that the people—and the government they elected—still don’t have their act together? Or concern that Lagos is where the rest of Africa is headed: a massive vase shattered into innumerable pieces, each wielded by someone incomprehensible to the next, each trying to fit their piece to another, never agreeing on the symmetry of the vase or where each piece belongs?

Is it to affect indifference? God put us all on this earth, and it is wise to leave to him to sort us all out when the time comes—emotional responses, whatever they may be, will have not an iota of difference?

All such questions flow naturally as you accept the Lagos embrace of rain, humidity, exhaust smoke, bodies, rubbish, swamp, car horns—all fermented together in the Lagosian air.

The city, however, does not give you answers. These are questions to figure out on your own.

Chaos Expressway

Leaving mainland Lagos and heading to the affluent Ikoyi and Lekki peninsula areas you will likely travel, in some part, on the Lekki–Epe Expressway. This is where the tiny Suzuki Every, the typically beat down yellow Kombi minibus, Toyota Hiace, the Okada, the yellow 3-wheeler Maruwa, the large 26-seater bus—these being types of public transport vehicles that fight with private passenger cars on the Expressway all day.

It’s closer to truth to call the highway the chaos expressway.

It’s not only the stand still traffic jams, on a road that is only 30 miles at full length, that turn half-hour journeys anywhere else into four-hour nightmares, it’s also the ceaseless orchestra of car horns used as a warning of approach from the rear, or to say you are crowding my lane, because no driver on this indispensable highway trusts that the other driver will use their side and rear view mirrors or is paying attention.

In some sections the highway is a two lane thoroughfare in each direction, making four lanes. When traffic is at a standstill, the impatient denizens of Lekki often turn two lanes into five lanes going in one direction by driving on the road shoulder and the grassy transition to the roadside ditch or sidewalk that is landscaping in some other places.

The constant hustle

Besides the sensory overload; the noise, the smells, the humidity, the colorful sights—all staples of a visitor's existence in Lagos that can overwhelm, another thing that wears on a visitor is the constant need to be alert and on guard against the hustle. Lagos is fraught with emanations that it would be optimal if money changed hands during all kinds of interactions.

A lot of the hustling is innocuous run-of-the-mill micro retail on the go: smartphones accessories arrayed and pushed on a wheelbarrow, soda and water bottles in a crate, confectioneries wrapped in plastic on wicker baskets, wild nuts shrink wrapped four to five per package—incremental living at ₦200 ($0.12) to ₦1,000 ($0.70) per sell.

The hawkers carry on this trade on congested roads like Lekki-Epe Expressway balancing crates of sodas or loads of snacks on their heads, dodging close packed aggressively driven vehicles, selecting the requested product out of eyesight above their heads, taking money and making change on the run all at the same time.

But dealing with money changers on the side-streets in Lekki is high stakes. There is money on the line.

You exchange a couple of hundred dollar bills into bundles of Naira that will not fit your hip pocket much less in a wallet. You will walk out with that bundle onto a street where you encounter in rapid succession men, vital men of early adult age all the way to middle age, lounging around singly and in groups, looking as if there is no purpose to their loitering, but you know they are there for no other reason than to make money.

All feedback is that Lagos is a place where the unwary can lose their wallet, shirt and shoes in broad daylight at a wrong turn or if they are simply unlucky. With pockets bulging with currency, you wonder how much of a target you make. And if among eyes tracking you in your air walk cargo shorts, Livergy loafers and your plain T-shirt, there are some apt to resort to aggravated methods to relieve you of your cash so they can make their outing worthwhile.

But before the pockets can fill with Naira, a money changer must be engaged and the conversion be made.

The dealers are mostly from Northern Nigeria, Hausa men. The transaction takes place in multiple languages. Your fixer is a Yoruba speaker and speaks English. The dealers speak to each in a language(s) clearly not Yoruba, but command the necessary English to effect transactions. By their attire you think it is safe to assume they are Muslim; whether it is as devout practitioners or simply as part of the broader culture is an open question.

However, the permutations in your mind, notwithstanding the presence of your fixer, include the hope that the Islamic prohibition of interest charging on loans also means honest dealings in all financial transactions. You realize though that the advantage in the interaction is in favor of the money changers. There are simply many more of them and you are on their turf. You are certain they must have ways of signaling to make the advantage keep accruing to them.

The money changing negotiations happen at several levels: the actual rate of exchange, the fee if you want to collect cash or do a bank transfer, and the fee for bills that may be in bad condition.

Except in the last case, you see the money changer take an ok $100 bill, hold the bill in both hands at the tips of his forefingers and thumbs, turn it over and throw it down on the table and claim the bill has some damage. He will have trouble offloading it.

With the thumb-forefinger maneuver, he has put a small but visible rip in the bottom of the bill next to the silver strip. You can’t be sure whether the rip was in the bill before. You didn’t know you needed to scrutinize the bill before handing it over.

However, if you hand over four ₦1,000 notes, the dealer is willing to accept the ripped bill—make this minor hiccup go away. You counteroffer two ₦1,000 notes. He accepts and makes noises to the effect that he is doing you a favor because of the presence of your fixer.

This realization crystallizes when, with time, you replay the transaction in your mind on the drive away from money-changer central.

Two thousand Naira is about $1.30. In principle, the rip-off is annoying, for the chump feeling that attends the money changer's success in pulling off his con, in practice it is of little consequence. It can’t even be put down as a lesson learned. The last time such a transaction needed to happen was more than 10 years ago. It will take equally that long for an opportunity to put the lesson in practice in Lekki, if at all. The money changers will have different tricks by then.

Generosity

Lagos is not all hustle however. In this city of contradictions, where some skim to strip you of your last kobo, you will also find giving souls, truly generous people who will roll out the red carpet in welcome—picking you up at the airport with all your luggage and making all at their disposal available to you to include cooked sumptuous meals on occasion.

When visiting a place, where you sleep and what you eat can color your experience of the place. This is one area where Lagos, in the person of our hosts, shined. There are hotels, but nothing beats staying with a local resident to soak in a place as experienced by people living there.

And so this is Lagos—the giving city on the Atlantic, where a visitor can be swept through sensory overloads within the same hour: generous hosts, shady money changers, an unholy symphony of indiscriminate car horns and then calm—a seat on a breezy second-floor storefront balcony, watching the busy street scene below, sipping a cold can of Legend, Nigeria’s own stout.

That last one, a moment of pause and enjoyment of a local flavor is the exclamation mark to this trip.

Your imagery is brilliant Mac! I can fully envision the energy of Lagos! As someone from the Caribbean that have lived abroad for most of my adult life I can relate to the scrutiny we place upon returning to homeground. Thank you for sharing :)