How I came to read Kafka on the Shore on a bullet train

The bullet train, more aerodynamic landfish than machine, it may be simply the smoothest phenomenon on rails.

On a trip to Japan in the late summer of 2024, I brought with me two books: Buddenbrooks, by Thomas Mann, a German author, and Chronicle of a Death Foretold by Gabriel García Márquez, a Colombian author. I had started reading Buddenbrooks on the inbound flight, but I was thinking to immerse myself into the land of the rising sun, I had to read works by Japanese authors. Reading works by a nation’s authors offers insight into that nation’s culture and psyche; it tells the preoccupations of its youth, the fears of its adults, its traumas and triumphs, how the nation relates with itself within its social units from the nuclear family to the nation-state, how it relates with other nations—all that comes through in a work or other of fiction or nonfiction. All compelling stories are grounded in the realities of their settings, and one way to catch a glimpse into a nation's realities is through reading its authors.

On a hunt for a book on Japan

The only book by a Japanese author I owned is Snow Country by Yasunari Kawabata. I had started to read the book a couple of times before without seeing it to the end—it was never going to be a serious contender to make the trip to Japan. My edition is a 175 page Edward G. Seidensticker translation; not a long read. Other than that I am not a speedy reader, and maybe drawn to the book by the nationality of the author and his spare prose, and not so much the actual story, I had no other reason for not finishing in one sitting or two the previous couple of times I picked it up to read it. It is also a book written and published more than 60 years ago. I was visiting Japan in 2024. It is now a vastly different nation from the post World War II era nation reconstituted by America where Kawabata published the book(Before the mid fifties publication, Kawabata wrote and published the book in parts starting in about 1937).

When I got to Japan, I regretted not packing Snow Country and bringing it with me; but I also felt I needed to read a book set in contemporary times, touching on some of Japan’s forceful modernity and hi-tech glory. I began looking for a bookstore to buy books (The main character in the book I bought played music on discs on a Walkman, was driven around in a two seat Mazda Miata, and had a plastic Casio watch with an alarm and stopwatch. Mobile phones yes, smartphones no—I got none of the forceful modernity as I conceived it).

At the end of a detour to Osaka, and on my way back to Tokyo, I decided on a whim while I waited to board the Tōkaidō Shinkansen bullet train that Shin-Ōsaka Station would be the place to do the deed; the place to buy the book to dip my toes into the psyche of Japan. I wandered into a bookstore to find a book or two that would do for me for Japan what Brothers Karamazov does for me for Tsarist Russia. Although I have never been to Russia, reading Dostoevsky gave me some idea of the sensibilities of Russian society of the time such that I think I can recognize echoes and shadows of what is Russian in spirit: respect for hierarchy, the coexistence of the sway of the orthodox church and unbelief—faith on one hand and reason on the other, the stoicism, even self-deprecation, in the face of weather that can be brutal and not infrequent national turbulence, etc.

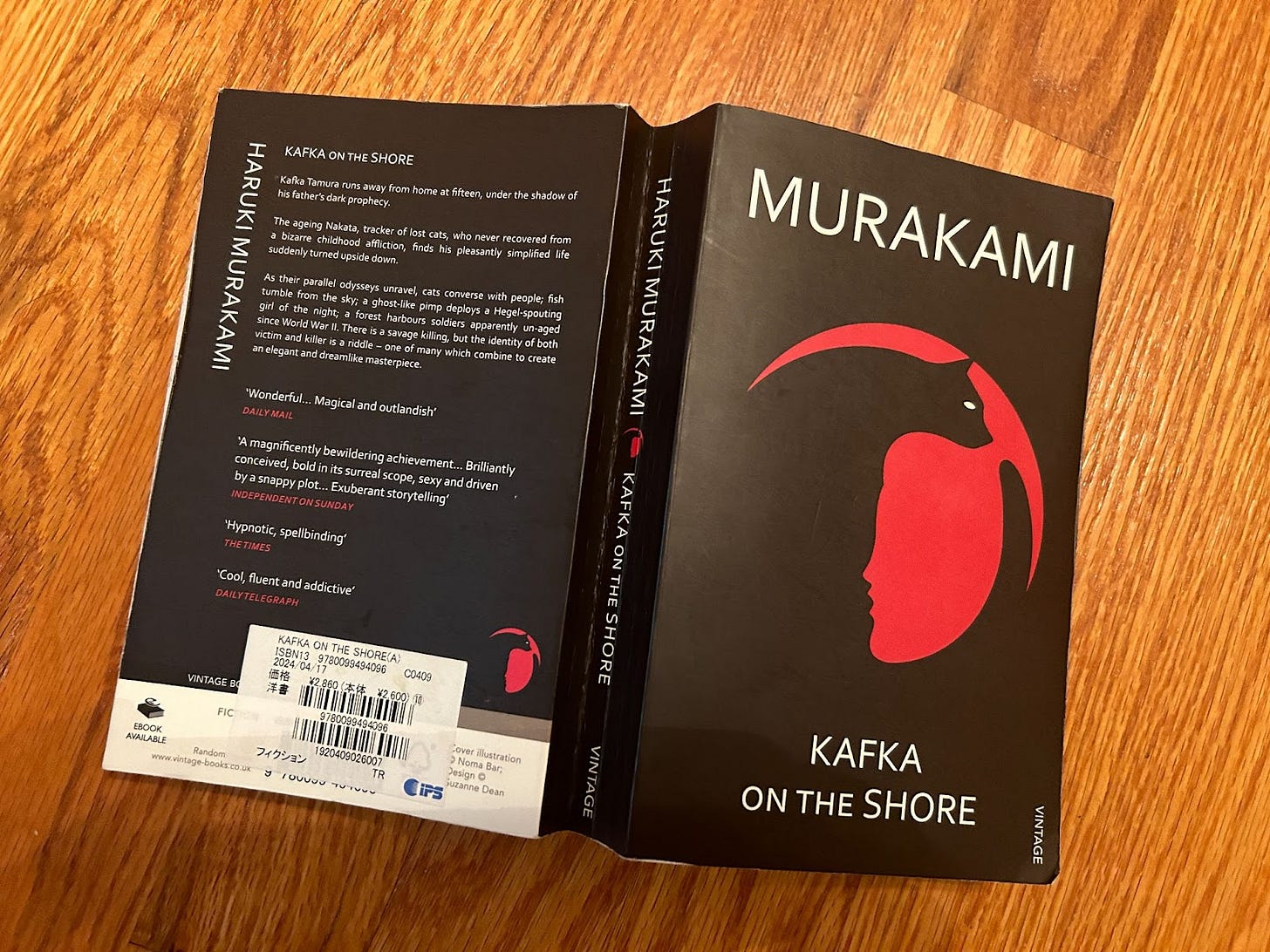

I did not go into the bookstore with particular titles in mind. With the sightseeing and moving around, I had no time to do in depth research to know what books would work for my purposes. The two books I eventually bought were random picks—I picked what was familiar and available. It is just as well that I did not have anything specific in mind; the bookstore only had a small selection of English language books related to Japan. I bought two: one an extended history of Japan, A History of Japan by R.H.P. Mason and J.G. Caiger—later, I found it had lukewarm online reviews as a work for a scholarly introduction to Japanese history, but might do for casual light reading; the second book was a novel—Kafka on the Shore by Haruki Murakami translated to English by Philip Gabriel. Murakami is a name I had heard of.

I knew he was a famous author but had never read him. I think name recognition was the factor in choosing his book. As for the history book—having settled on a work of fiction, I thought I needed a work of nonfiction to complement the fiction book. The particular history title was the only choice and only copy of the kind from among travel guides, books on etiquette, books on basic Japanese language and such. I hoped it would be engaging and provide interesting insights, although I elected to read the novel first.

Landfish

I flipped to the first page of Kafka on the Shore seated by a seaside-window of car number six of the 16 car Nozomi bullet train on the two and half hour trip from Osaka to Tokyo; the same journey by car takes seven hours. I mention the side of the car I sat because looking out the seaside windows toward the Pacific, I was foregoing the chance to see Mount Fuji about four-fifths of the way into the trip. On a clear day, it is possible to see Mount Fuji in the distance at a certain segment of the journey looking out of the mountainside windows of the train.

Besides the passing scene of the Japanese eastern countryside: farm fields, greenhouses, factories, villages, suburbs, towns, rivers etc., the bullet train is itself a scene—cutting through the landscape, more aerodynamic landfish than machine, it may be simply the smoothest phenomenon on rails. It glides as if on air when, in fact, it is metal-on-metal friction pushing it forward by way of one of the oldest technologies in the world; a wheel running on something, in this case a wheel on a metal rail, and 128 solid steel wheels on each train.

The bullet train is actually not one machine, it is many trains, for sure in hundreds of machines, perhaps even in the low thousands if we consider different operators across Japan. I had become curious on the way from Tokyo to Osaka seeing the steady frequency of trains going in the opposite direction. I tried to keep a mental count, but kept losing track and ended up believing we had passed no more than in the top single digits number of trains. On the way back from Osaka to Tokyo I kept a tally on my phone—I counted 48 trains travelling in the opposite direction towards Osaka, and that was on a Saturday, on only one line between Osaka and Tokyo going in one direction. Assuming the same number of trains were traveling in my direction, we are already at 100 trains on a single line.

Reading Kafka on the Shore in Translation

In between counting trains, trying to catch the passing scene outside my window, the pacific ocean every now and then, stolen glances past other passengers on the other side of the car to the mountainside windows to see Japan’s green spine, digging into the first pages of Kafka on the Shore was more perusal than actual reading. The novel promised a fast read and its narrative seemed easy to follow. The sentences are simple and ideas easy to grasp, yet I wished I could read it in its original Japanese. I think it is near impossible to understand or appreciate nuances of a language and an author’s craft when reading a work in translation. Whenever I read translations to English of any of the Zambian languages I grew up speaking, I feel a certain fluorescence of color around the words is lost. I feel it is like a serving of spaghetti rinsed off of its seasoning; it will provide the needed calories, but something fundamental about the meal is lost—it is the case sometimes that hunger is a secondary reason for eating a meal; meals can be entertainment or distraction from boredom. In the same way, I imagine a translated work loses, for a non-speaker, something that is inherent in its original language of writing and publication.

As I ruminated, I had to look up again from Kafka on the Shore. We were approaching the location where Mount Fuji is orthogonally situated relative to the train and rail tracks. It was anticlimactic. Even those seated by the mountainside windows could not see the mountain through the haziness of the atmosphere. Denied this once in a lifetime act of seeing the famous mountain from a famous train—the scenery outside my window seemed to repeat itself—farm field, river, greenhouse, factory, village, suburb, town etc., with only the order changing, and Tokyo getting closer by the minute. So I settled in and gave all my full attention to Kafka on the Shore.

(My next post will be about my reading of Kafka on the Shore)

You managed to take me with you to the streets and countrysides of Japan, vividly offering me an serving of sights and sounds, smells and textures of the Land of the Rising Sun. Looking forward to the second part.

Quite enjoyed this! My daughter read this book last year and when she adopted her kitten and was looking for a name, I suggested Kafka… we now have a one and a half year cat named Kafka 😻